The difference Between a "HOLDER" and a "HOLDER IN DUE COURSE:" The Law & Practice in Uganda

Introduction

The position of a holder is very important in the law of banking

in the operation of bills of exchange because it is they that these instruments

are issued to by a drawer. It is from a holder that we get the type “holder in

due course” but both are embodied in the Bill of Exchange Act.[1] This paper will look into how one becomes a holder in due

course, the rights and privileges that accrue from this position and then I

will give the differing provisions from the English law to that of Uganda’s

law.

Definitions

A bill of exchange is

an unconditional order in writing, addressed by one person to another, signed

by the person giving it, requiring the person to whom it is addressed to pay on

demand or at a fixed or determinable future time a sum certain in money to or

to the order of a specified person or to bearer[2].

According to Section 1(i) Bills of Exchange Act[3] , “a holder means

the payee or endorsee of a bill or note who is in possession of it, or the

bearer of a bill or note.”

A holder in due course is

defined under S.28 Bills of Exchange Act[4] as “a

holder who has taken a bill, complete and regular on the face of it, under the

following conditions namely, that he or she became the holder of it

before it was overdue, and without notice that it had been previously dishonoured,

if that was the fact and that he or she took the bill in good faith and

for value, and that at the time the bill was negotiated to him or her he or she

had no notice of any defect in the title of the person who negotiated it.”

The difference between a holder and a

holder in due course lies in the requirements and rights and liabilities, and

then the payee holder can never be a holder in due course. The requirements

that we draw from the definition of a holder in due course include; that a holder

in due course must be a holder a negotiable instrument that was taken: for

value, in good faith, without notice that it is overdue, dishonoured, or

encumbered in any way, and, bearing no apparent evidence of forgery,

alterations, or irregularity.

Requirements of a holder in due course

A holder in due course

must be a holder[5]

Every holder of a bill is presumed to be

a holder due course[6],

until fraud or illegality is admitted or proved in the acceptance, issue or

negotiation of the bill.[7] The

presumption is rebuttable by a party alleging that the holder, in question is

not a holder in due course presenting evidence to prove that the requirements

of a holder in due course have not been satisfied. Vaughan Williams L.J in Talbot

v Jan Bons[8] made

a quotation that set out the law in England on cases coming under section 30(1)

(equivalent to section 29(1) cap 68) Bills of exchange Act. Where he said that:

“ the presumption in such a

case is that the instrument was given for good consideration” and goes

on to say that “if the defendant intends to set up the defence that

value has not been given, or that the instrument was originally obtained by

fraud the burden of proving that lies on him”

However, if in an action on a bill, it

is admitted or proved that the acceptance, issue or subsequent negotiation of

the bill is affected with fraud, duress, fear, force or illegality, the burden

of proof is shifted. This means that the holder of the bill will not be

regarded as a holder in due course unless he proves that he was not a party to

fraud, illegality or duress and that he obtained the bill for valuable

consideration, in good faith without notice of defects to the bill. It is for

this reason that in Hassanali Issa & Co. V Jeraj Produce Store[9], Duffus

J.A observed that“if a duress, force or illegality was proved as having

affected the bill judgement would have been entered for the defendants.”

Holder in due course for value and in good faith

The presumption of good faith and value is that; every

party whose signature appears on a bill is prima facie deemed to have become a

party to it for value.[10] Then

every holder of a bill is prima facie deemed to be a holder in due course; but

if in an action on a bill it is admitted or proved that the acceptance, issue

or subsequent negotiation of the bill is affected with fraud, duress, or force and

fear or illegality, the burden of proof is shifted, until the holder proves

that, subsequent to the alleged fraud or illegality, value has in good faith

been given for the bill.[11]

The general rule is provided under s 28(3) of the Bill of

Exchange Act[12] which

provides that A holder (whether for value or not) who derives his or her title

to a bill through a holder in due course, and who is not himself or herself a

party to any fraud or illegality affecting it, has all the rights of that

holder in due course as regards the acceptor and all parties to the bill prior

to that holder.

To Holden[13],

‘the rule applies where a cheque affected by some fraud or illegality is

negotiated to a person who has no knowledge of such irregularity and who

becomes a holder in due course. Although the transferee has knowledge of the

irregularity and has not given value for the cheque, he has all the rights of

the original holder in due course as regards all parties prior to the holder.’

A holder in due course without notice

To acquire the status of a holder in due course, a holder

must take the instrument without notice. This is in accordance with the

Bill of Exchange Act[14] which

states that, “A holder in due course is a holder who has taken a bill,

complete and regular on the face of it, under the following conditions that he

or she became the holder of it before it was overdue, and without notice that

it had been previously dishonored, if that was the fact.”

Notice of a defective instrument is given whenever the holder

has actual knowledge of a defect; or has received notice of the defect from

bank identifying serial number of stolen checks; or has reason to know that a

defect exists, given all of the facts and circumstances known at the time.

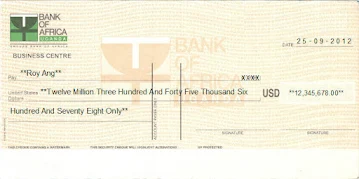

The bill must be

complete and regular on the face of it

An incomplete bill is either undated,

does not state an amount or lacks a required signature for example an

endorsement. A bill which merely lacks an acceptance is not incomplete.[15] Once

any essential element of form is lacking, the transferee cannot be a holder in

due course.[16]

However, Section 2(4) of

the Bill of Exchange Act provides that a cheque is not invalid by

reason that it is not dated. And section 11 gives the holder

power to fill in the date. Lord Denning in Arab Bank

Ltd V Ross[17]observed

that though a cheque without a date is not invalid, it is not complete and

regular for purposes of Section 28 because regularity is different

thing from validity. A cheque is regular on the face of it whenever it is such

as not to give rise to any doubt that it is the endorsement of the payee. Lord

Denning further observed that as when an endorsement will give rise to doubt is

a practical question which is a rule, better answered by a banker than a

lawyer. Bankers have to consider the regularity of endorsement every week, and

every day of week, and every hour of every day; whereas the judges sitting in

the court have not had to consider it for the last twenty years.

Shelter principle

Acquiring the holder in due course status in the shelter

principle[18]which

states that;

‘A person who does not qualify as a holder in due course can, nonetheless,

acquire the rights and privileges of a holder in due course if he or she

derives his or her title to the instrument through a holder in due course.’ To

qualify as a holder in due course under the shelter principle, the following

rules apply: The holder does not have to qualify in his or her own right. The

holder must acquire the instrument from a holder in due course or be able to

trace his or her title back to a holder in due course. The holder must not have

been a party to a fraud or illegality affecting the instrument. The holder

cannot have notice of a defense or claim against the payment of the instrument.

Rights and privileges

of a holder in due course.

A holder of a bill has

the right to sue on the bill in his or her own name[19].To discharge a bill there must be

payment to the holder in due course, which must be by or on behalf of the

drawee or accepter.[20]In

case of failure to obtain payment on the bill, the holder in due course has the

right to enforce payment from all prior parties to the bill.

A holder in due

course takes the bill free from equities, he can defeat any defences arising

from defects in title, or from the dealing between prior parties to the bill. As

provided for in s 37(b) Bills of Exchange Act[21],

the holder of a bill where he is a holder in due course , holds the bill free

from any defect of title of prior parties as well as from mere personal

defences available to prior parties among themselves and may enforce payment

against all parties liable on the bill. It goes without say that a holder in

due course can enforce payment notwithstanding defences available to prior

parties among themselves and despite defects in the title of any prior party.

Where the discounter is a holder in due course, he can enforce the bill of

exchange against a drawee who has accepted it in the mistaken belief that a

forged bill of lading attached was genuine[22].

This was derived from Guaranty Trust Co. of NewYork V Hannay & Co.[23] where

it was held that the plaintiffs did not, by presenting the bill of exchange for

acceptance, warrant or represent the bill of lading to be genuine, and that the

defendants were not entitled to recover back the money paid to the plaintiffs.

Section

37(c)(i)&(ii), provides that a holder of a bill

whose title is defective and he or she negotiates the bill to a holder in due

course, that holder obtains a good and complete title there to and payment

thereon discharges the drawee from liability under the instrument. However a

banker marking a cheque with a reason for dishonour clearly prevents subsequent

parties from becoming holders in due course.

Under S.28(3)[24], a

holder in due course can pass a good title with all his rights to a holder,

whether for value or not, who is not himself a party to any fraud or illegality

affecting it. The rule applies where a cheque affected by some fraud or

illegality is negotiated to a person who has no knowledge of such irregularity

and who becomes a holder in due course. He then negotiates the cheque to

someone who has knowledge of the fraud or illegality but not himself a party

thereto.

Scrutton LJ stated in Slingsby

And Ors V District Bank Limited[25] that

a holder in due course might not be affected by an alteration not apparent.

According to S.63(1) Bills of Exchange Act[26],where

a bill is materially altered but the alteration is not apparent, and the

bill is in the hands of a holder in due course, such a holder may avail himself

of the bill as if it had not been altered and may enforce payment of it

according to its original tenor. Material alteration may be in the form of

alteration of the date, the sum payable, the time of payment, the place of

payment and where a bill has been accepted generally, the addition of a place

of payment without the acceptor’s consent[27].

The holder in due course however has the

right in every case where a wrong date is inserted, if the bill subsequently

comes into his hands, the bill shall not be avoided thereby, but shall operate

and be payable as if the date so inserted had been the true date,[28] the

holder in due course has the privilege of inserting a date on the bill.

Another right of a holder in due course

can be found in the provisions of S.19(2) Bills of Exchange Act[29],where

an inchoate instrument which is converted into a bill, but not within a

reasonable time or in accordance with the authority given is negotiated to a

holder in due course is valid and effectual for all purposes in his hands and

he/she may enforce it as if it had been filled up within reasonable time and

strictly in accordance with the authority given.

A holder in due course

is also privileged not to be affected by dishonours. Section 35(5)

provides that where a bill which is not overdue has been dishonoured, any

person who takes it with notice of the dishonour takes it subject to any defect

of title attaching thereto at the time of dishonour, but nothing in this

subsection affects the rights of a holder in due course. Where a bill is

dishonoured by non-acceptance and notice of dishonour is not given, the rights

of a holder in due course subsequent to the omission are not to be prejudiced

by the omission.[30]Therefore it

is upon the drawee to make it visibly clear on a bill that it has been

dishonoured by non-acceptance otherwise the rights of a holder in due

course will still remain unaffected by this because of the privilege of

lack of notice of dishonour created under the provision.

In section 54(1)(b) the

holder in due course is privileged that drawer of a bill is precluded from

denying to a holder in due course the existence of the payee and his then

capacity to endorse. The

maker of a promissory note is also precluded from denying to a holder in due

course the existence of the payee and his or her then capacity to endorse[31] So when

a payee indorses a bill to a holder in due course and it is defected, he can

bring an action against the drawer but the drawer cannot deny the existence of

the payee or his capacity to endorse.

A holder in due course is also

privileged under section 55 which provides that where a person

signs a bill otherwise than as a drawer or acceptor, he thereby incurs the

liabilities of an endorser to a holder in due course. As such, this provision

serves to protect the interests of a holder in due course as well as curtailing

people who wish to hold out as drawers yet they are not.

Differences between Ugandan law and English law

The section on inchoate situations[32] in

Uganda’s Bill of Exchange Act was repealed under The Finance Act, 1970,[33] which

incorporates the Britain’s Bill of Exchange, 1881. The section repealed provides

that; ‘Where a simple signature on a blank stamped paper is delivered by the

signer in order that it may be converted into a bill, it operates as a prima

facie authority to fill it up as a complete bill for any amount the stamp will

cover, using the signature for that of the drawer, or the acceptor, or an

endorser; and, in like manner, when a bill is wanting in any material

particular, the person in possession of it has a prima facie authority to fill

up the omission in any way he or she thinks fit.’

The UK Consumer Credit Act, 1974 now

incorporates the sections on holder in due course and negotiable instruments

from Bill of Exchange Act of 1882 and these are provided under section 123 to

125 of the UK Consumer Credit Act.

The act disqualifies a holder in due course who takes a

negotiable instrument except for a cheque contrary to section 123.[34] Section

29 of the Uganda Bill Of Exchange Act was excluded by the Consumer Credit Act,

1974 section 125(1)[35] which

incorporated the holder in due course. This provides that “person who

takes a negotiable instrument in contravention of section 123(1)[36] or

(3)[37] is

not a holder in due course, and is not entitled to enforce the instrument.”

Section 29(2) of the Uganda Bill Of Exchange Act was amended by

the Consumer Credit Act, 1974 section 125(2)[38] which

incorporated the holder in due course. It is provided there under

that “Where a person

negotiates a cheque in contravention of section 123(2), his doing so constitutes

a defect in his title within the meaning of the Bills of Exchange Act 1882.”

Conclusion

The laws of Uganda[39] have

protected a holder in due course and it is nearly impossible to impeach him of

his rights to payment on a bill except for instances where fraud, duress, force

or illegality have been proved against the holder in due course which would

disqualify him automatically as a holder in due course. The rule was developed

so that negotiable instruments could be moved from bank to bank without concern

over the defenses the endorser might have in the underlying transaction.

However, I would disregard the law in holding the bonafide endorser

liable and say it ought to protect every bonafide party

involved in the passing of the negotiable instrument.

"A family which Reads together, passes together"

AHIMBISIBWE INNOCENT BENJAMIN

(Entertainment Lawyer)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment